A new wave of cancer research is emerging from laboratories with results that are both scientifically striking and emotionally galvanizing: nanoparticle-based vaccines are preventing and even eliminating aggressive cancers in mice. These experimental vaccines are reshaping what scientists thought possible in immunotherapy, offering a glimpse of a future where the immune system can be trained to recognize and destroy tumors before they take hold.

How the nanoparticle vaccines work

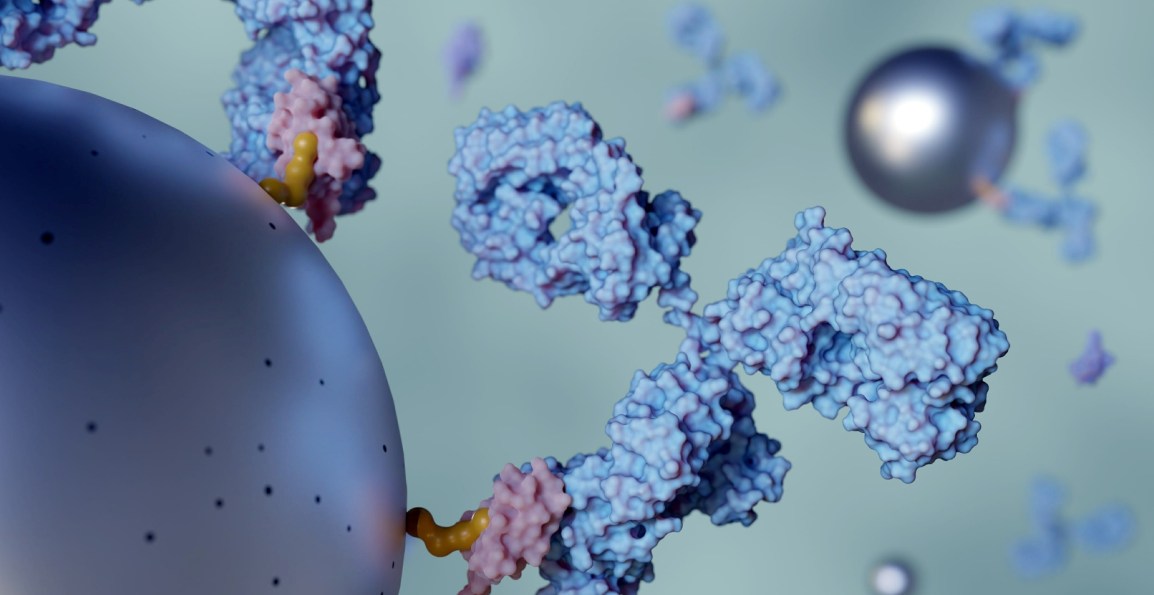

At the heart of this breakthrough is a deceptively simple idea: package cancer‑specific antigens inside engineered nanoparticles and pair them with a powerful “super‑adjuvant” that turbocharges the immune response. The nanoparticles act as delivery vehicles, ensuring the antigens reach immune cells efficiently and trigger a multi‑pathway activation that traditional vaccines struggle to achieve. This approach not only stimulates robust T‑cell responses but also builds long‑term immune memory, enabling the body to recognize and attack cancer cells if they reappear.

Results in mice: prevention, treatment, and halted metastasis

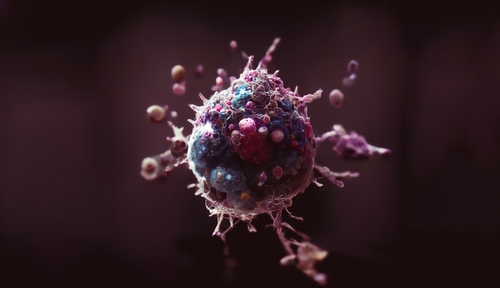

Across multiple studies, the results have been extraordinary. In experiments led by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the nanoparticle vaccine prevented several aggressive cancers—including melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and triple‑negative breast cancer—with up to 88% of vaccinated mice remaining tumor‑free.

Even more striking, the vaccine didn’t just prevent tumors; it also stopped metastasis, the often-deadly spread of cancer to other organs. In some cases, metastases were reduced or eliminated entirely.

Another study described the vaccine as a “super vaccine,” noting that it not only prevented cancer but also generated a powerful, durable immune response capable of halting tumor growth and recurrence.

Why this matters for the future of cancer treatment

Cancer vaccines have long been a scientific ambition, but the challenge has always been generating an immune response strong enough to overcome the evasive tactics of tumors. Nanoparticles appear to solve several of these hurdles at once:

- Precision targeting — delivering antigens directly to immune cells

- Enhanced potency — thanks to the super‑adjuvant design

- Broad applicability — effective across multiple cancer types

- Durable protection — long‑lasting immune memory reduces recurrence risk

These qualities position nanoparticle vaccines as a potential foundation for universal cancer vaccines, a concept once considered purely aspirational.

The road ahead

While these results are limited to mice, they represent a major leap forward. The next steps—testing safety, scaling production, and eventually moving into human trials—will determine how quickly this technology can transition from the lab to the clinic. But the momentum is undeniable: researchers have demonstrated that the immune system can be trained, with the right tools, to defeat even the most aggressive cancers.