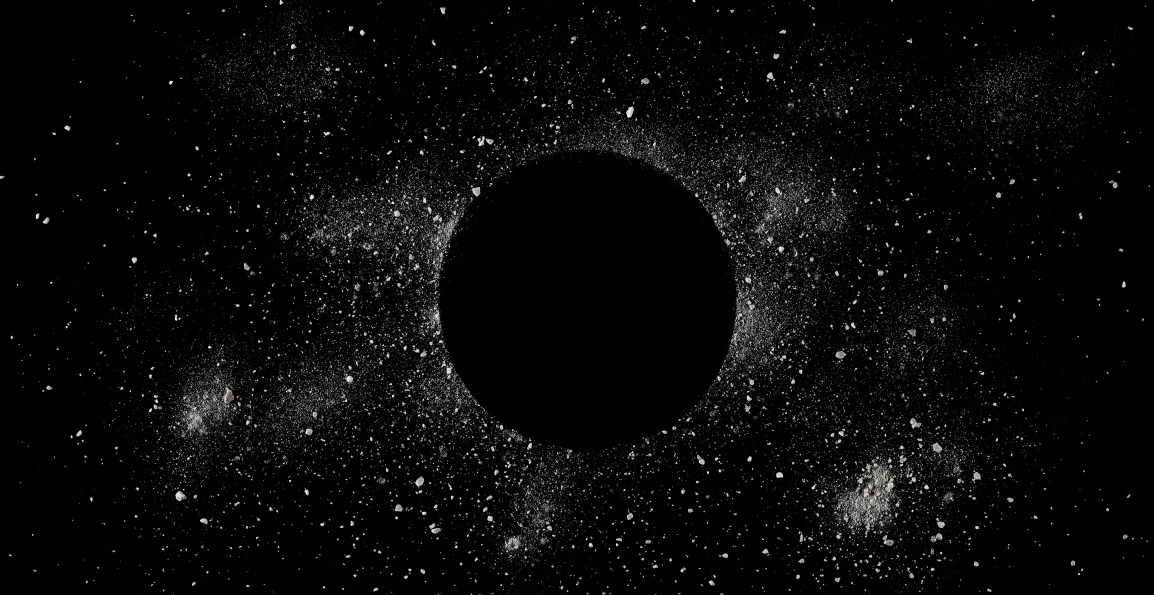

Astronomers may have finally glimpsed dark matter, with recent gamma-ray observations offering the strongest evidence yet of its existence. In late 2025, researchers at the University of Tokyo reported signals from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope that match long-standing predictions of how dark matter particles should behave, potentially marking the first direct detection of this elusive cosmic substance.

The Invisible Framework of the Cosmos

For nearly a century, scientists have wrestled with the mystery of dark matter, a hypothetical form of matter that does not emit, absorb, or reflect light. Its existence was first proposed in the 1930s by Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky, who noticed that galaxies in the Coma Cluster were moving too fast to be held together by visible matter alone. Later, in the 1970s, Vera Rubin’s studies of galactic rotation curves reinforced the idea that something unseen was exerting gravitational influence. Today, dark matter is thought to make up about 85% of the universe’s mass and roughly 25% of its total energy content, yet it has remained undetectable by conventional means.

The Recent Breakthrough

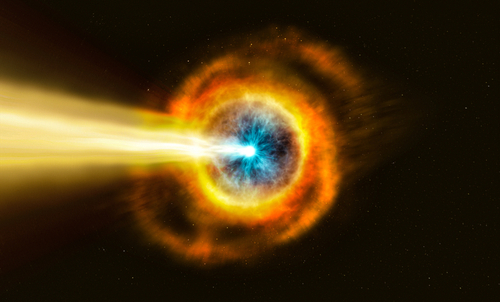

In November 2025, astronomer Tomonori Totani of the University of Tokyo analyzed 15 years of Fermi Telescope data and identified a halo of high-energy gamma rays surrounding the Milky Way’s center. These gamma rays align strikingly well with theoretical predictions of weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs)—a leading candidate for dark matter. According to models, when WIMPs collide and annihilate, they should release photons at specific energy levels. The observed glow matches these expectations in both intensity and spatial distribution, making it one of the most compelling leads in decades.

Why This Matters

If confirmed, this discovery would represent humanity’s first direct observation of dark matter, a milestone comparable to the detection of gravitational waves in 2015. It could:

- Validate decades of theoretical physics by confirming WIMPs as real particles.

- Revolutionize cosmology, offering insights into galaxy formation and the large-scale structure of the universe.

- Open new physics beyond the Standard Model, since dark matter does not fit neatly into existing frameworks.

Skepticism and Next Steps

Despite the excitement, scientists remain cautious. Gamma-ray signals can also be produced by astrophysical sources such as pulsars or black hole activity. Distinguishing between these and genuine dark matter annihilation requires further analysis. Independent teams will need to replicate the findings, and future instruments—such as the Cherenkov Telescope Array—may provide higher-resolution data to confirm or refute the claim.

Conclusion

Dark matter has long been described as the “invisible glue” holding the universe together. The recent gamma-ray detection may finally have given us a glimpse of this hidden substance, marking a turning point in astrophysics. While skepticism is warranted until the evidence is independently verified, the possibility that we are witnessing dark matter for the first time is both thrilling and profound. If confirmed, this breakthrough will reshape our understanding of the cosmos and open new frontiers in physics.