Scientists have discovered that moss can survive months on the exterior of the International Space Station, revealing its extraordinary resilience and potential role in future space habitats.

Moss in the Harshness of Space

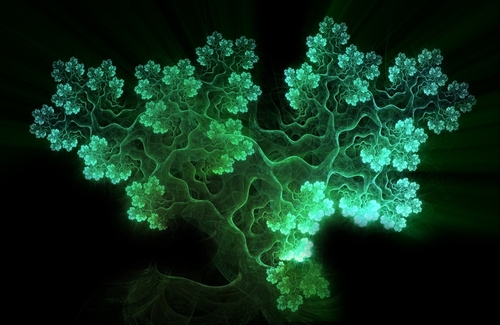

When Japanese researchers attached samples of Physcomitrium patens—a common laboratory moss—to the outside of the International Space Station (ISS), they expected most of it to perish. Space is unforgiving: a vacuum with extreme temperature fluctuations, intense ultraviolet radiation, and virtually no oxygen. Yet, after nine months of direct exposure, much of the moss remained viable. In fact, over 80 percent of spores germinated successfully once returned to Earth.

This experiment, published in iScience, tested three developmental stages of moss: juvenile filaments (protonemata), specialized stem-like brood cells, and sporophytes (structures that encase spores). While the juvenile moss failed under the harsh UV bombardment, the sporophytes and brood cells endured, retaining their vitality and reproductive potential.

Why Moss Matters for Space Exploration

Moss is not just a curiosity. Its survival outside the ISS suggests it could play a role in closed-loop ecosystems for long-term human habitation beyond Earth. Mosses are simple plants that:

- Photosynthesize efficiently, producing oxygen.

- Absorb and retain water, helping regulate humidity.

- Tolerate extreme environments, from volcanic fields to Antarctic tundra.

If moss can withstand space, it may serve as a biological pioneer for habitats on the Moon or Mars, contributing to air recycling, soil formation, and even food webs. Researchers emphasize that understanding the resilience of Earth-born organisms is crucial for expanding human habitats beyond our planet.

Lessons from Earth’s Toughest Survivors

Mosses thrive in places where few plants can: Himalayan peaks, lava fields, deserts, and polar ice. Their ability to endure desiccation and radiation makes them ideal candidates for astrobiology experiments. The ISS study confirms that moss spores, much like bacterial or fungal spores, can survive long-term exposure to outer space and remain reproductively viable.

This resilience also raises intriguing questions about panspermia—the hypothesis that life could spread between planets via spores or microbes hitching rides on asteroids. Moss’s survival lends weight to the idea that life forms might endure interplanetary journeys.

Future Applications

The findings open several possibilities:

- Bioregenerative life-support systems: Moss could help astronauts recycle air and water in space habitats.

- Terraforming research: Studying moss survival may inform strategies for seeding life on Mars.

- Material science: Understanding how moss withstands radiation could inspire protective coatings or biomimetic designs.

Conclusion

The moss clinging to the ISS is more than a scientific curiosity—it is a symbol of life’s tenacity. By surviving nine months in the vacuum of space, Physcomitrium patens demonstrates that even the humblest plants may become vital allies in humanity’s quest to live beyond Earth. As researchers continue to probe its limits, moss may prove to be one of the first green pioneers of extraterrestrial ecosystems.